Gold in the Cargo Muchachos

History of gold mining in the Cargo Muchacho Mountains and the mining town of Hedges, California.

Lew Marcrum

10/2/202514 min read

THE SPANISH COLONIAL ERA

In the early 1600s the Spanish were well established in Mexico and in what is now the American southwest. Their last outpost of civilization was the pueblo of Hermosillo (Pitic), in western Sonora. They had also made a presence in California, notably at Santa Barbara and San Bernardino. Hermosillo was reasonably well supplied with the trappings of civilization by long trade routes from Vera Cruz and Mexico City, but California was still isolated except by sea around Cape Horn or the long Pacific route from Manila in the Orient. An overland route from Hermosillo to California was desperately needed, and there was no lack of adventurous Spaniards willing to take up the challenge in their personal searches for “God, Gold and Glory”, not necessarily in that order.

After acquiring a tentative peace with the Pimas and Papagos a Spanish military post was built at Sonoita in modern southern Arizona, and eventually a mission at San Xavier del Bac. Scouts had learned that to the north was a waterway which led west toward California. This was the Gila River which afforded a relatively easy and sure route as far at the Colorado River. Depending on the time of year, the Gila could be traveled by water using improvised boats or barges. Another tenuous truce had to be formed at the Colorado between the Spanish and the Quechan (Yuma) and Yaqui tribes.

At the confluence of the Gila and Colorado Rivers the Spanish soon built two new missions in hope of converting the local populace to the Catholic Mother Church. These were the Misión de Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción, and the Misión de San Pedro y San Pablo de Bicuñer, about six miles away. The rest of the relatively short route to the California missions was fairly safe and uneventful, except for the ravages of the scorching desert.

In their travels the Spanish never missed an opportunity to search for their second most important quest, GOLD. The local Native Americans had lived in the area for many generations, and undoubtedly were intimately acquainted with every mountain, wash and boulder. This was information the Spaniards could not hope to learn in a lifetime of independent prospecting. So with typical Spanish efficiency they found the best way to achieve their goals quickly was to grab a few local inhabitants and “interrogate” them sufficiently to find out the location of any gold deposits, then go make their claims on the yellow metal. More often than not, this method worked quite well.

The Spanish gold seekers were shown gold-bearing ore from a small, dark, and very mineralized range of mountains not far west of the Colorado River missions. There they found a few veins of gold-bearing quartz and red hematite rich enough to mine. They brought in experienced miners from Hermosillo, as well as using native forced labor as much as was practical. They named their mine the Cargo Muchacho, after the boys who brought them the first ore samples. Soon the whole mountain range was given the same name, which it bears to this day.

The Spanish mined the Cargo Muchachos for many years until Spain gave up her colonies in the New World. Later, Mexicans continued to mine until the ore proved not worth the cost to get it. While prospecting the area for new diggings, the Mexicans located and established mines to the north called the Padre, the Madre and the Oro Cruz. These were worked for a few years until it became uneconomical with their technology, then the entire Cargo Muchacho range was abandond...for a while.

After the US-Mexican War of the 1840s most of present western United States became American property. The discovery of gold in California brought untold thousands of prospectors and would-be gold miners swarming all over the western mountains and deserts. This included the Cargo Muchacho mountains.

The old Spanish mines were looked over with new interest. A company made another attempt to rework the old Cargo Muchacho Mine, but it was soon abandoned once again as uneconomical. The Padre and Madre were more valuable but not worth the investment necessary to make the desired profits. The Oro Cruz area to the north appeared the most likely for a good return on investors' money.

During the waning years of the Old West era working a mine in the desert was not easy. Operating a mine required a lot of money, so investors had to be found. Men had to be hired, machinery and tools brought in from suppliers, water supplies found, buildings constructed, mills, crushers, cyanide leach systems built, experienced blasters found, chemicals and explosives located and stored safely. Wagons and mule teams were necessary to haul all this from Yuma, over almost non-existent roads axle deep in dust and sand in Summer and mud in winter.

HEDGES, REQUIEM FOR A MINING TOWN

In 1877 the Union Pacific Railroad completed a line from Yuma to Los Angeles, which had a water and fuel stop at a place called Ogilby, California. Ogilby was only a few miles south of the Cargo Muchacho Mountains, and the mines therein. This attracted the interest of some investors far more wealthy than the small shovel-and-pan miners. Freight could be brought from Yuma or Los Angeles, to be dropped off at Ogilby then hauled by wagon the few miles to the mines. One of those investors was a man named C.L. Hedges who bought out all holdings in the old Oro Cruz mines, and named his new company the Golden Cross (Oro Cruz) Mining and Milling Company. Hedges brought in stamp mills and crushing equipment. He also brought in miners and their families from Yuma, as well as many Mexican laborer families. Hedges built living quarters for his workers, and the town of Hedges was born.

The little mining town of Hedges started modestly enough, boasting a population of thirty or forty miners and laborers. Soon some brought their families from Yuma, to build houses and create a real company town. With the help of the rail-head at Ogilby the fledgling metropolis found it much easier to expand than most tiny desert mining settlements. The miners were paid well for the times, and it was easy to obtain goods, even luxury items, usually available only in larger cities. Clothes, canned foods of every variety and good liquor were all easily had. Pure potable water was brought by wagon from Ogilby. Hedges even boasted a hospital and at least one asphalt paved street. All these things made life more bearable for the families, but nothing could relieve the awful desert heat, the dust, the glaring sun, occasional lack of water and the terrible isolation. Good wages were gained at a very dear price.

THE LIFE OF A MINER

A miner's life may be called many things, but it is never boring. Some say mining gets in one's blood, and I believe that from personal experience. It's like an addiction. It's one of the more dangerous occupations, and for that reason there's always the excitement of never knowing what this day will bring. This is especially true of the underground crews, who develop a certain fatalistic camaraderie somewhat akin to soldiers in combat. Every day after their pre-shift meeting they once again go down into the bowels of the earth with no guarantee they will ever return. At the end of their shift, when they again breath the fresh air of the outside world, there is a visible release of tension. Who can blame them for having a few drinks with their friends after work. And on the far side of the tails dump, across the wash, there was a discretely hidden brothel for those who wished to get their refreshment there.

Miners in the old days were a tough breed. There were no OSHA or MSHA regulations or inspectors to oversee the daily mine operations, so many times men were asked to do jobs that would be unthinkable today. Accidents were frequent, and safety rules were practically non-existent. Mechanical accidents and falls were common. It's the geology of that range that most underground rock is extremely cracked and faulted so all underground drifts in the Cargo Muchachos are shored, meaning they are lined with wood or sheet metal ceilings to prevent rock falls or cave-ins. sometimes making it borderline as being amenable to excavation at all. This made for a lot of stress on miners working deep underground in the mines.

The biggest danger to the Old West miners was actually none of the above, but the creeping Grim Reaper of silicosis, known as "miner's desease" in those days. In the era of dry-stamp mills a miner's life expectancy was around five years. Everyone knew this but everyone expected to be the exception. Mining paid much more than most other occupations of the time, so there were always men available to fill the places of those who went to an early grave.

Hedges, CA, around 1900. Looking west toward El Centro

Remains of two rooms of the brothel. More to the left.

Cams and shafts of a three-stamp battery. Cams turned on a horizontal axle rotated by a steam engine and belt drive. Cams raised the shafts and weights and dropped them from a variable height, thus crushing the ore below. Dry-stamp mills put lots of dust and silica into the air.

And graves there were. Many of them, all unmarked and their occupants long forgotten. At this late date we can't know how many died of miner's disease, accidents or other afflictions nor how many were family members who succumbed to the harsh conditions of a desert mining town. A few are very small and most likely the last resting places of children. Regardless, it's so sad to see so many lying unknown and unmourned forever under the hot desert sands, accompanied only by an occasional lizard or rattlesnake in the night and the lonesome howl of a coyote in the distance and the haunting sigh of the desert winds.

Hedges has two cemeteries, one for Catholics, one for Protestants. These are a few of the unmarked graves in the Protestant cemetary. There are many more at Hedges, and at least as many down at Ogilby.

Spanish Colonial soldiers exploring the Gila River Valley.

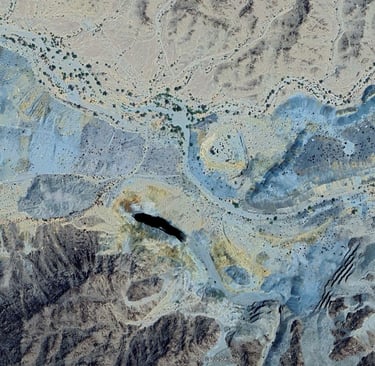

Northern Cargo Muchacho Mountains as seen from Olgiby.

Life in Hedges wasn't nearly as bad as most other desert mining towns of the time. After the railroad from Los Angeles was completed travel and communication with the outside world was easy, due to the rail stop at Ogilby. Trains going either direction passed at least once daily so there was little feeling of total isolation. It was convenient to get to Yuma most any day to visit friends and family there, and all the niceties of the world were available in Los Angeles to be dropped of for pickup at Ogilby. Fresh, canned and preserved foods of all varieties could be easily had, and the miners' families took great advantage of that fact.

Thousands of metal cans lie rusting in the trash dump of Hedges. A few show the use of an actual can opener, others the punch of a butcher knife, but the majority were opened by knocking out the zinc-sealed fill hole on top.

There are cans of every shape and size.

At it's peak Hedges had over 3000 residents and that many people need certain services. Potable water was hauled from Ogilby by wagon, and a rudamentary hospital was built to handle first aid for mine injuries and illnesses. Serious cases were taken to the hospital in Yuma.

The medical building in Hedges. One of the few buildings with standing walls left in the town.

Nearly all others have been pulled down and destroyed by vandals.

There is evidence of at least one asphalt-paved street in Hedges, but of what time period I have no idea. All things considered, Hedges was far more comfortable and convenitent than the vast majority of other desert settlements. The one major drawback to living there was, and remains, the blistering heat of the desert Summer.

THE GOLD OF THE CARGO MUCHACHOS

Country Rock of the Cargo Muchachos.

In more recent years mining geologists discovered that there is still gold in the Cargos, and a lot of it. But it comes with some problems. First, the gold is mostly not in the usual intrusive zones of different color that can be traced and mined easily underground, but in the surrounding matrix, or "country rock", and impossible to differentiate by sight whether it's ore or waste. Second, except for occasional vertical high-grade red hematite veins, the ore is very low in gold content, ranging as low as 0.002 to 0.010 ounces per ton, which usually requires cyanide heap-leaching and an enormous amount of haulage. Third, the ore bodies are more valuable at depths not accessible for open-pit mining

The doré from these mines runs around 60-75% gold, the rest mostly silver with a bit of copper. The color has a greenish tint due to the silver content.

The country rock of this range is horribly cracked and faulted. It's like trying to tunnel under a huge pile of boulders, and special shoring techniques are essential. Even with the best modern shoring technology, the miners risk their lives every day to haul out the ore.

THE SAD LEGACY OF HEDGES

Besides the miserable and dangerous working conditions, the stifling heat and thirst of the desert and the untimely deaths of many miners and their family members, desert mining always leaves scars and evidences for future generations to ponder.

When the southwest desert lies untouched for many years the unshaded rocks and stones develop what has been called "desert varnish". It is a brown coloration that gives the untouched desert it's natural hue. The deeper brown the color, the longer the rock has lain under the sun's harsh radiation. Desert varnish affects different types of rocks with varying colors of brown but eventually nearly all will succumb to the fierce radiation.

Desert Varnish

The photo above shows a bit of desert floor stained brown by the harsh sun. The white stone near the sop is a piece of massive quartz, which is affected less than most other rocks by radiation. There are a couple other pieces of quartz with more brown, indicating they have been at this location for many years longer than the white one. These stones have lain here for hundreds, thousands, maybe tens of thousands of years or more untouched by man or beast. This is what made desert tracking easy for Apaches, and the gleaming white quartz "float" was an old west prospector's dream.

I'm talking about desert varnish to emphasize the point that EVERYTHING we do in the desert leaves a scar, even walking across it. And mining leaves scars that will take nature untold thousands of years to recover it's normal state.

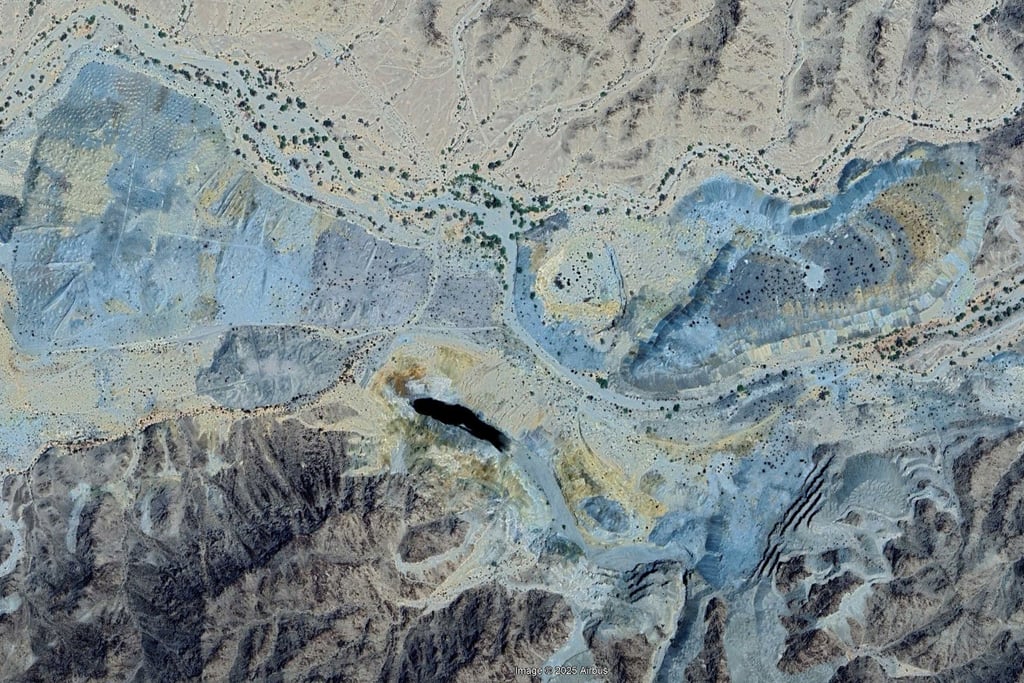

Bliish Gray Mine Waste from Oro Cruz Mine

In the photo above the waste rock from underground is strikingly different in color from the sun-browned mountains. It will remain a scar and eyesore on the mountains for at least a thousand years, probably more.

Ecological Catastrophes

Mining companies have always been very good at drilling, blasting, milling, extracting gold....and leaving.

Modern mining laws say that when a mine is shut down and abandoned the mining company must remove all equipment and buildings, haul all remains of leach pads and waste dumps to refill the open pits or underground shafts, and raze everything to the ground to make it look as natural as possible. But there is a problem: this process is expensive, and it brings in ZERO revenue. As a result the companies usually make a short show of it, bulldoze some buildings, push some waste rock around and leave with shafts and pits left partially or wholly unfilled.

One of the largest mining operations in the Cargo Muchachos. This is a Google Earth view showing an abandoned mine and incomplete cleanup. An early attempt at open pit mining is evident as well as a huge cyanide leach pad, a large waste dump and an adit for underground mining filled with stagnant water. All the blue-gray color is newly-exposed rock, waste or tails, and will be visible as a desert scar for many hundreds of years.

The most visible evidence for the existence of Hedges is a row of four huge steel tanks east of the townsite and very close to the Oro Cruz mine. These appear to be of later date, possibly the late 1930s or 1940s, after the townsite's decline and the disappearance of most or all it's former inhabitants.

Steel tanks of Hedges. Oro Cruz Mine in background.

Originally there were four large tanks. The left one is nearly totally destroyed and the second is damaged well beyond repair. Some, including most park personnel, say they were cyanide leach tanks. Not knowing their exact extraction process I can't say for sure, but I have doubts about that assessment.

Mining always requires a lot of water, and water in the desert is a precious commodity. Though they could pump water 14 miles from the Colorado River, water that could be reclaimed in processing was like money in the bank. I believe these tanks were mill tails thickeners, the likes of which I have seen many times.

In mill vat processing the gold is dissolved with a water/cyanide solution. After extracting the gold with activated charcoal the spent solution and thin mud slurry is dumped into one of the tanks. A slow agitation process revolves on the tank bottom to prevent the mud from becoming solid and impossible to move. Once the tank is full to a predetermined level the slurry flow is switch to the second tank, and the first is left of clarify. When the solids are mostly near the bottom and the water above is somewhat clear, it is siphoned off or pumped back into the mill for reuse.

Reclaiming water and thickening solids takes time. That is why there are four large tanks, to be used in sequence. When as much water as possible has been reclaimed from the first tank and the slurry has reached 50% - 60% solids, it can be dumped into the environment with little danger of cyanide contamination. But...here was a problem.

Closer view showing how tails was dumped and flowed down and to the right.

Disaster of Dumping Tails

I mentioned above that I think these tanks are from a later era, and here is why: at least half of the site of Hedges as it was in it's prime was completely COVERED with dumped mill tails, some places several feet thick. This could only have been done after most of the residents had already left.

Cyanide, CN, is one of the most common molecules in nature, especially prevalent in plants. Tobacco, spinach and certain other dark green vegetables contain far more cyanide than is allowed by law to be dumped in spent mill tails. Sodium cyanide, NaCN, used in gold processing degrades rapidly, and there is little chance of the tails dumps at Hedges being toxic. But they are barren and plant life may take hundreds of years to grow back normally.

Mill tails dumps covered the mining town of Hedges nearly a hundred years ago, and still almost NOTHING grows there.

Nature trying to reclaim Her own.

The Paradox of Gold

Why do men covet gold? Men have fought and died for it. They have killed their brothers and friends for it, fought wars, conquered other peoples and endured unimaginable hardships to scratch it from the earth. And for what?

Except for some limited modern technological purposes gold is intrinsically useless other than for personal adornment. The earliest men found they could not eat it or wear it, they found it worthless for tools and weapons, yet they all wanted it. WHY?

Men want gold for the same reason they want modern paper currency: because OTHER MEN WANT IT! They want a lump of mostly useless yellow metal or an absolutely useless slip of printed paper because they can leverage the greed of others to get what they want, and that leverage is POWER!

Unfortunately, many times that search for wealth comes at way too high a price.